The Swansea Review

Blog

Who We Are

We are Swansea Review’s blog. Here you will find some of the writing from creative writing students.

Look out for interviews and extracts coming in the next few weeks.

Follow our Student Ambassadors as they share and explore Writing at Swansea.

It begins with an idea.

It’s true. A simple spark that creates a thousand possibilities. Take a moment and think about it. Are you ready? It’s a simple question.

What is creativity?

Don’t give me a simple response. Creativity is... Blah, blah, blah.

This morning while I was running around my kitchen making sure that dogs were suitably fed and kids were suitable socks. My eyes caught sight of the dying daffodils that I bought a week or so ago. The formerly bright yellow petals have shrivelled to a pathetic mustard colour. Blackened veins have appeared, and the now bowed heads have a distinctive crispy crunch on the edges. I feel bad that I hadn’t noticed their descent into decay sooner, but I did think that’s great material for a poetical piece. And then I wondered were does inspiration come from? What is it that makes people create Art?

All day it made me extra curious, and I like sharing my curiosity. You know, planting little seeds and hoping for something to grow and optimistically answer me back. So I thought I’d ask a bunch of young minds.

‘I just write, and I don’t know. I like to write stories.

My dad wrote me two stories but won’t get them published - they are really good. He was in prison, and he wrote me a story which is a bit babyish. But the one he wrote to me when I was twelve was about how my family came together, and I loved that.

I write too. I wrote one was about a giant, a scary giant. Which I kinda based on my Uncle. I wanted people to have sympathy and connect with the giant. It’s a story for kids. It’s about a giant who is big and scary, and people avoid him, and he tries to make friends but gets it wrong, and he makes a boy cry. The giant gave the boy a teddy to comfort him, and they became friends.

I write songs and rap as well. I started rapping in the shower; it just came to me all the words.’

RP, Year 9 pupil at Bryngwyn Secondary School.

It made me think maybe it’s true the words just come. I don’t question it. If anything, I’m very happy with that arrangement, and long may it keep happening.

Over the coming weeks, I will ask many questions about creativity and inspiration because everything needs a starting point to grow.

March 10th, 2023

RRG

Joining Swansea University's Creative Writing MA

Your Questions Answered

What happens with Enrolment?

You will get an enrolment pack via email in September with lots of info.

Read it carefully.

There will be forms you need to complete online.

You will need to collect your Student ID Card from the Library

How does Full Time VS Part Time work?

Full time

2 Year Part time

3 Year Part time

Year 1

Semester 1 (Oct-Jan)

Compulsory Module

Module

Semester 2 (Feb-May)

Module

Year 2

Semester 1 (Oct-Jan)

Compulsory Module

Module

Semester 2 (Feb-May)

Module

Dissertation (May-Sept)

Year 1 Semester 1 (Oct-Jan)

Compulsory Module

Module

Semester 2 (Feb-May)

Module

Year 2

Semester 1 (Oct-Jan)

Compulsory Module

Module

Semester 2 (Feb-May)

Module

Year 3

Dissertation (May-Sept)

Semester 1 (Oct-Jan)

Compulsory Module 1

Compulsory Module 2

Module

Semester 2 (Feb-May)

Module

Module

Module

Dissertation (May-September)

Module Choices?

You have to complete 2 COMPULSORY modules

You need to choose 2 of these options

Long Fiction 1

Poetry 1

Wrtiting for Stage

You cannot complete Long Fiction 2 or Poetry 2 without completing Long Fiction 1 or Poetry 2 first.

Module Choices

Then you can choose ANY 4 of these options

Long Fiction 1

Poetry 2

Writing for Stage

Creative Non-Fiction

The Art of Short Story

Long Fiction 2*

Poetry 2*

Screenwriting

Writing Radio Plays

Writing for the self

Where am I going to be based?

What room?

How long are the lectures?

How do you get Assessed?

How does giving Feedback work?

Final Notes

Read the Handbook

Download Canvas App

Get Familiar with Campus

Ask if you are stuck

Get involved

And most importantly,

Write And Enjoy the Process!

A live reading by

Akosua Darko

PhD Student

I am woman hear me roar

Akosua Darko was born in Ghana and is from the Akyem and Akwapem tribe. Moving to England at the age of nine and grew up in Milton Keynes. Akosua completed a BA in English Literature and Creative Writing BA and a Master in Creative Writing at Swansea University.

Loving the University-life so much, Akosua is continuing to study and is currently in the 3rd year of a Creative Writing PhD, where Akosua is clashing Ghanaian culture and British culture to make entertaining, thought-provoking poetry.

Akosau is the poet of The Black Honeybee.

Swansea Review Online Vlog

Richard Burton Archives

Thousands of archived voices

There is a treasure trove of information where stories are just waiting to be told. And what if I told you that they are all in Swansea waiting for you? Would you perk up with interest and say, ‘Go on…’

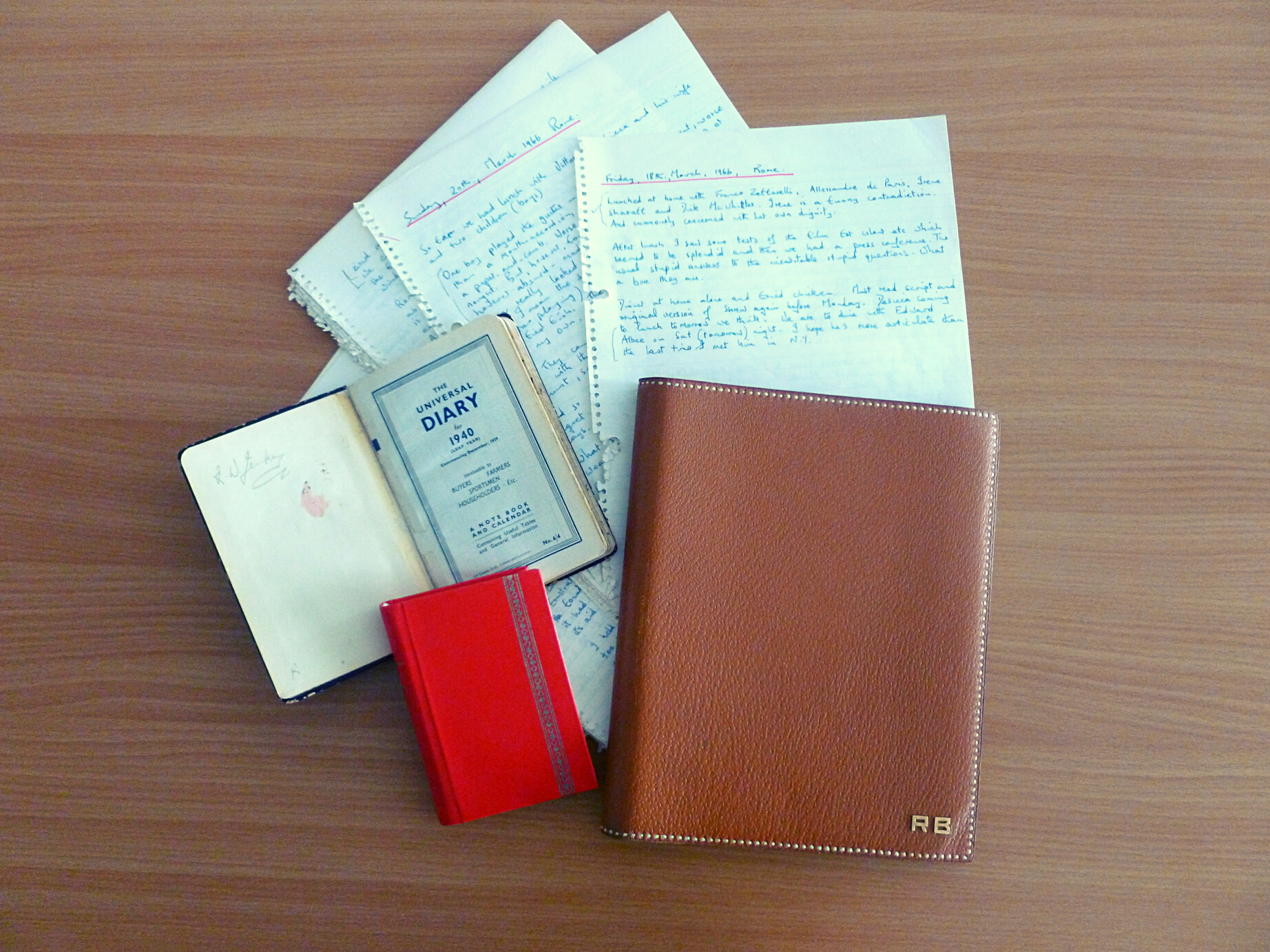

The Richard Burton Archives are located on level 1 west within Swansea University’s Singleton Campus Library. 1. 8 kilometres of records are stored on colossal wheeling shelved units (they kindly let me have a go) with jewelled coloured volumes containing a vast amount of information from business records of Swansea, to student magazines from the twenties, to Richard Burton’s diaries. This is a place of wonder, entertainment and history colliding in a purpose-built space.

With so much historical information to preserve, the archivists dedicate so much attention to flood, fire, smoke, dust and mite, theft, temperature and humidity prevention. You name it; they have a plan to prevent it as these are unique and one of a kind, and by one of a kind, I mean the only copy in the World in many cases. I’ll repeat that, the only one in the World.

Material of local, regional, and national significance. Collections from the Vivian, Dillwyn, and Morris families. The staff laid out an array of material for me to see. Amy Dillwyn’s diary was one of them. Her handwriting and the rectangular shapes sliced out of her diary entries amazed me. For Amy’s eyes only, what did she write? What didn’t she want to remember? What a story that could be.

There are records from the Roman Catholic Church of St. David’s Priory, Swansea and the Methodist Circuit of Swansea and Gower. Records from the South Wales Coalfield, life in the nineteenth and twentieth coalfield valleys just waiting to be discovered and storified. The organisations were created from the trade unions, institutes, and societies, to the documents of hundreds of individuals connected to the mining community—a million and one individual stories waiting to be discovered and told to new audiences. As a writer, I know that is like striking a pot of untapped inspiration, and I defy anyone not to find something in the Archives that might spark an incredible story.

University records - societal, minute books, departmental records, prospectus and press cuttings, photos, architectural plans, student life. Personal papers of noted individuals connect with the university. Documents that show the aims, objectives and achievements that have shaped the University to what we know today.

Papers of Raymond Williams are, too, housed in those sandy-coloured boxes on shelves nestled between deep forest greens, rich reds of ruby and burgundy leatherbound covers, next to deepened sapphire blues mixed with eye-popping mustard yellow covers. The oldest archived incidentally is a piece of parchment from the 15th Century.

In the Reading Room, all laid out for me was a silk playbill with frail pink ribbon detail around the edging handstitched from Theatre Collection from the late 19th/early 20th century. Account records of Reading Palace Theatre, A copy of the script of King Macbeth from Raymond Williams's collection to Ruby Graham’s photograph album from the 1920s. Ruby Graham was a producer and director at Swansea Little Theatre; she was also an alumnus of Swansea University, and many of the photographs show her as a popular, vibrant, charismatic young woman on Langland Beach with her friends. There are even copies of all the past student magazines and newspapers.

As well as Richard Burton's photographs with Dame Julie Andrews from the film Camelot, a copy of Burton’s film script of 1984. I got to hold his 1940s pocket diary, where he noted his cricket batting averages amongst scribbles about fishing and his various thoughts. Given my fondness for the ‘golden age of Hollywood’ and family connection to the Actor Stanley Baker, it felt odd and somewhat intrusive to flick through. My mother later that day remarked, ‘Do you remember me telling you about the time I fell in my Grandmother’s house and Stanley caught me? Well, Richard was there too. Everyone/s dead now, who can verify that.'

It occurred to me that whilst my mother could verbally recount a story about famous movie stars, all I could think about was all thousands of past voices. Quietly preserved under the considered eye in Swansea University Archives.

Much of the catalogue is online, and should you hit a speed bump, the incredible archivists are so knowledgeable that they can point you in the direction of what you are looking for. The visit to the Archives was indeed a privilege. But I can’t urge you enough to go and visit for yourself to see what stories you might discover for yourself.

Contact

The Richard Burton Archives is open to the public, students and staff.

Visits to the Archives are by prior appointment, the current opening hours are 9.15am-16.15pm Tuesday-Thursday. The archivists are available to answer enquiries Monday to Friday – please contact archives@swansea.ac.uk or 01792 295021

Or you can follow them on Twitter @SwanUniArchives

Main Archive website -

https://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/richard-burton-archives/

Libguides -

https://libguides.swansea.ac.uk/richardburtonarchives

Blog - https://swanseauniarchives.home.blog/author/swanseauniarchives/

Items viewed.

- Richard Burton diary, 1940 (RWB/1/1/1)

- Amy Dillwyn diary, 1867-68 (DC6/1/4)

- Script from King Macbeth, c.mid 20th century. Raymond Williams Collection (WWE/2/1/3/4)

- Screenplay from 1984, Richard Burton Collection. (RWB/1/8/16)

- Photograph of Richard Burton and Julie Andrews in Camelot. 1960 (RWB/1/4/2/12)

- Silk playbill for All That Glitters. Theatre Collection. [late 19th century - early 20th century]. LAC/106/E/15

- Reading Palace Theatre treasury book no.3 detailing weekly income and expenditure also used as a scrapbook for playbills and programmes. Feb 1944-Jul 1945, LAC/106/D/9

- Ruby Graham photo album, 2021/13. c. the 1920s

Creative Writing Youths

Spotlight on Future Writers

We chat to four young inspiring writers about what they loved to read and write

What's your story about?

It's basically this bizarre thing where you have to read between the lines almost to get to it. This person is running away from something, and there are mists everywhere, and nothing really makes sense. And there are things screaming and running away, and the person collapses, and people run all over them. There is like one line of speech at the end, and ooh, spooky or something.

What inspired you to write?

Honestly, I can't remember, but I felt inspired to write in the middle of the night.

(I say) - Its always in the middle of the night, isn't it?' The group all nod with a chorus of 'yeah's.'

What do you read outside of school?

Outside of school, I read a lot of books by Leigh Bardugo called The Grishaverse. It's very fantasy and magic, but there are also some really depressing moments.

'As there should be' gets whispered by one of the group, and they all start laughing.

The whole style of writing, the way she writes characters and directions, is really inspiring. I also read action books and fantasy. I made it through The Shining by Stephen King. I also read a bit of true crime and Wikipedia pages of like really gruesome murder cases, but I think it informs what I have written. Some of it might be a little... wait, no! Don't include that bit! (They all start laughing) You know ways of torture, as you do.

Eruption of giggles.

CG, Year 9

Something wasn't right, that much was clear from the beginning. Dark mist began to fill the area, enveloping everything in sight like a deadly fog. Everything had been so cheerful, so normal, so happy...

What had gone wrong? Or...

Did nothing actually go wrong, and this is how things had always been?

Their deep, heaving breaths broken up by occasional coughs were the only sound to shatter the eerie sheet of silence. The clouds of pale mist pouring from their mouth stood out against the fog like the sun in the dark void of space. Their knees had begun to buckle with exhaustion, just barely keeping then upright.

They had to keep running.

Fresh waves of goosebumps and terror washed over their body, bewitching their aching legs to work, to run. Beads of sweat ran down their frightened face, mixing with a steady stream of tears to create large droplets that fell to the invisible ground.

Where did they all go?

What are all the echoing screams of terror? Are they in danger? What even is this dark fog?

...

..... all were questions that had no answers.

What's your story about?

It's about Gonks who take over Christmas because of a grudge against Santa Claus. They are also in love with Mrs Claus, The Gonks want to steal Christmas from him. And they want to steal his wife.

What inspired you to write?

I was in Home Bargains or B+Q with my mother, and there were gonks everywhere. And we were chatting and said, 'They are everywhere; it's like they are stealing Christmas'. And then we saw one; you know those mini statues of Santa? Well, there was one sitting on top of it. So I was mulling it over at home then after a while, I had this whole storyline going around in my head. So I wrote most of it down, I have a plan at home.

So, do you have a full plan already?

Yeah, it's just getting around to writing it, especially with school.

What do you read outside of school?

Mostly fantasy and fiction stuff, like Percy Jackson, and Harry Potter. The Grishaverse I'm reading at the moment. Hunger Games is great

DB, Year 9

Gonks: The Christmas Takeover

We’ve all heard of the Christmas gonk. When you hear the word gonk you probably think of the little bearded fellowswith the massive pointy hats. But for those people that have never had the experience of seeing a gonk, they are small menwith big bushy beards and big, tall hats that completely cover their eyes and forehead but have their round bulbus nosessticking out the bottom. They have long arms and long lanky legs but a small round body. A gonk is never seen without its hat, and it is said that anyone who has seen them without their hats either didn’t live to tell the tale or was injured so badly that they cannot remember what it looked like (they get a little upset if you take off their hats!!).

Gonks are very protective of their allies and possessions which is why people put up decorations of them to protect them from evil around Christmas time. Gonks are also notorious for being very mischievous when they are left unsupervised or even when they are supervised (as you’ll find out in this book). Theres one thing that you should know about gonks before you read this book… they absolutely hate anyone or anything that they think has copied them. This could be having the same beard as them or even just looking similar to them. The only exception to this, is of course other gonks. If they see something or someone that they think has copied them there could be several different reactions from the gonks. These could range from giving them a dirty look to destroying said thing with their bare hands until they are satisfied that it no longer looks like it has copied them. Trust me when I say that you do not want to see a gonk angry!!They may be just over a foot tall, but they can fight someoneten times their size when they’re angry.

Gonks live in tribes in different places. This story is about the village-side gonks who live near a small village called Glitter-Ville which is in the middle of nowhere. The gonks live in the woods next to the village and even though they aren’t supposed to, they always go into the village to nose around or steal something, so they know the village pretty well. All gonk tribes have their own colours that they wear, this tribes’colours are red, purple, green and blue. The only person who doesn’t wear these colours is Captain Brian, their leader and the oldest out of the tribe, whose colours are gold and silver. A gonks tribe is its brothers and occasionally its sisters, the girl gonks of the family live in a separate tribe on the other side of the village. If a gonk wants to get married it will go to another tribe that they are not related to and try to get a girlfriend. They usually see other tribes at the annual gonk meeting where every gonk in the country joins together in one of the tribes’ homes for a massive get together that usuallyinvolves a lot of food, alcohol and partying. These parties are only once a year, but they can last several days. The longest party went on for over eight days and only ended when the drink and food ran out and they all went back to their own homes to carry on the parties there! That year the people in the village wondered why there were so many tiny footprints going off in all directions in very wiggly lines, most leading to tiny people shaped prints in the snow as if a little person with a big pointy had fallen over multiple times on their way home. You can see why they are only once a year. The party startsaround a week before Christmas day which means that the next one is about two weeks before our story begins.

What's your story about?

It's about a scenario in world war 1. Sammy is standing in a battle; he's exhausted, he's holding a gun and looking around, and a soldier runs up to him and puts his hand on his shoulder and turns around and shoots. He thinks he's the enemy, but it's one of his side, it's about the PTSD and the Trauma, and then it's him panicking and going through his head. I guess...

Like Flashbacks? (Question asked from the group)

Sort of, but... like, you know it's not real. He sees his mum going, 'What have you done?' Even though she's back at home. Basically, thinking, 'Oh, what would my mum say?'

(I ask) Hallucinating?

Yeah, yeah! Oh my Gosh!

What inspired you to write?

Umm, I was really inspired by anything. It was actually an English assessment.

Oh, so it was something you had been tasked to do?

Yeah, But I went about deeper.

Did you do any additional research for it?

No, just knowledge I already had from school and drawing on things I already knew

What do you read outside of school?

I'm not a conspiracy theorist, but I do like reading books about unsolved mysteries. There was one specifically about statues bleeding, and I thought that was cool. I also read a lot of... I don't know if this counts as "proper" literature I read a lot of Japanese Manga and Anime.

LD, Year 9

Your poem, UNTITLED or?

It will probably be called Overwhelmed.

Yes! We have a title. So, why poetry?

I just like the meaning of poetry. I like the little storyline, and I just love it so much.

What inspired you to write?

It's to do with my anxiety and my umm... and my overwhelming moments and thoughts. So it's telling a truth for me.

Do you find it gives you an outlet for you?

Yeah, I think it does. A place for me to express myself and put that anxiety in a way.

What do you read outside of school?

Fantasy. I love anything with magic and creatures, Fairy Tale lands.

Do you think they influence your poems?

Yeah.

How?

Cos' with the fairy tale stories they are quite long and I can contain it to a shorter form. I like short stories. I tend to favour those things with Anxiety, and I can focus on it. It helps me focus. If it's shorter and I can keep it clearer in my mind.

KC, Year 9

Overwhelmed

I’m overwhelmed,

I was happy then I turned sad,

Suddenly everything has gone bad,

I am breathless, it’s hard to breathe,

To calm down I have to be thinking,

While my hand is shaking,

My thoughts are surrounding me,

How can that be?

Interview

Laura Morris

Rhys Davies Prize Winner 2022

What does creativity mean to you?

As a secondary school English teacher, I’m always trying to encourage my students to be creative. They are used to rules, and often, while writing, they will raise their hands and ask questions such as, ‘can I write in present tense?’ or ‘does my poem have to rhyme?’ I usually respond with comments like, ‘you can do what you like. There are no rules. Be creative!’ I suppose, ultimately, I view creativity as freedom. Yet, I recognise that certain rules can encourage you to be creative. For example, things like word limits, time constraints and deadlines can force you to go in directions you might not have chosen.

Where do you get your inspiration from?

I generally start with a ‘voice’ and then build a character from that. I’m rubbish with plot. I’ve realised that I don’t pay much attention to plot in books and films; I can never remember what happens! But I remember the mood and atmosphere, I suppose. I remember the way the book or film made me feel, and I think perhaps that’s usually what’s going on with my own writing; it’s often plotless but has a definite tone.

What are you currently reading?

I’m currently reading Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado.

What are you working on?

I’’m working on a collection of short stories. I have maybe five or six stories

that I’m happy with. I’m working on some new ones and thinking about

how they all might fit together.

Who are your favourite writers? Or your favourite book(s)? And why?

If you had asked me this question ten years ago, I would probably have said Ian McEwan and Raymond Carver, but today I mostly read female writers. I love Wendy Erskine’s and Lucy Caldwell’s short story collections. I really enjoyed the Saba Sams’ collection, ‘Send Nudes.’ I think it has great energy. I also like Ottessa Moshfegh and Cathy Sweeney.Their writing is wonderfully strange and compelling.

How does your writing process work?

I don’t plan my short stories, really. I type straight into a blank Word document (or Google Docs these days) and see what happens. On the weekend, I often write in bed, before I’ve showered, got dressed and woken up properly. I think still being in a dream-like state helps. I will just write, often changing perspective – from first-person to third-person and back again, from past tense to present tense and back again, until I think I’ve found the right way to tell the story. I recently changed a short story from first-person, past tense to second-person, present tense and it found a new energy; it was worth the work. I don’t work efficiently at all. I never have. I’m an excellent procrastinator. I often work on more than one story at a time, and then if I am stuck with one story, I can move onto another and come back to the stuck one later. Sometimes a walk will unlock the thing I was stuck with, but sometimes it will take six months to find the key. I’m learning that is my process, and I have to trust it. I wish I had a different way of working, but I don’t think I will change now!

How do you find time to write?

It is difficult to find time on top of teaching, but I have learned to give my writing at least the same attention that I give my job. I was listening to Eimar Ryan – one of the founders of Banshee Press – on The London Writers’ Salon podcast the other day. She said, ‘it is so much easier to let yourself down than to let other people down. I short circuit that instinct and do my own work first. The other work will get done.’ I think this is good advice. I often have planning and marking to do on the weekends, but I make sure that I write first. I am also lucky to have decent school l holidays, which means even if I haven’t written for a few weeks, I can usually allocate a block of time to it during my break. Basically, I can’t be precious about it. I have to write when I can!

What did winning the Rhys Davies prize mean to you?

While I really hoped that my short story ‘Cree’ would be on the Rhys Davies Prize shortlist, I never dreamed I could win it. It is such a great prize, and I really enjoyed meeting all of the other shortlisted writers at the launch in October 2022. It was such a joyful and positive evening, celebrating the short story here in Wales. All of the stories in the Parthian collection are wonderful. Winning has given me ‘permission’ to talk about my writing and allowed me to feel it’s worth sticking with. I spent the prize money on taking more writing courses. I suppose I just want to get better.

What advice would you give to new or emerging writers?

Every writer will tell you to read more and write more. They are right. There are no shortcuts. Listen to the New Yorker podcast, read the work they publish, but read the smaller magazines too. The Lonely Crowd here in Wales is great. Banshee, based in Cork, is excellent. Read emerging writers. Ask yourself how far away from that standard you are. Learn from them. Be honest with yourself. Take classes and join workshops. Be open to advice and criticism. I am in an online writing group. We meet every three weeks or so. The feedback I get from the group members is invaluable.

Laura Morris has an MA in Creative Writing from Bangor University. Her work has been published by Honno Press and broadcast on BBC Radio 4. Recent short stories have appeared in The Lonely Crowd and Banshee. She now lives in Cardiff where she is the Head of English at Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Bro Edern.

Acorns and Oaks

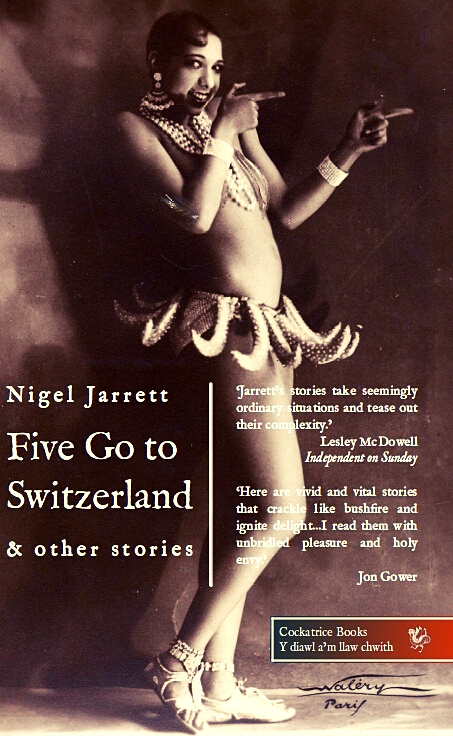

An interview with Nigel Jarrett

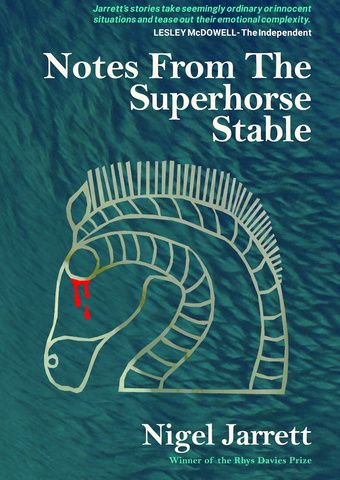

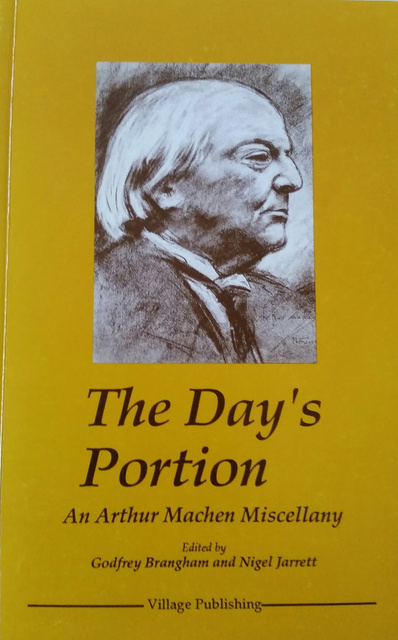

Wales's premier award for short fiction, the Rhys Davies Prize, has been made just ten times since it began in the early 1990s in memory of the celebrated Welsh novelist and story-writer. Nigel Jarrett was one of the early winners. His latest books are a fictional memoir, Notes From the Superhorse Stable, and a fourth story collection, Five Go to Switzerland. Here, he reflects on the writing life and other literary matters.

What does creativity mean to you?

Creation is the opposite of repetition; so, creativity is the making of something new, something original. But, for a writer or any other artist, it's a complex subject. I write short stories, among other things, but I don't claim to have revolutionised the form. Better writers than I have wrought changes that lesser ones like me take or leave. Most of us are happy with established models so that we can express ourselves in the content, and that's the extent of our originality. It's what we have to say.

At base, though, creativity gives the creator the thrill of having produced something that wasn't there before, be it story, painting, or chair. The character and quality of stories, paintings, and chairs and the nature of what they mean are for others to evaluate. The satisfaction of having produced them has, for their creators, long given way to a continuation of the creative process.

It's the same for creators everywhere else; comedians, for example - telling an old joke is repetition; devising and telling a new one for the first time is creative and original.

Where do you find your inspiration?

Anywhere and everywhere. I can identify the provenance of everything I've written. It might be lodged in personal experience or a personal view of things, or in events happening beyond me. My second story collection, Who Killed Emil Kreisler?, included stories located in Sweden, Africa, France, Austria, and America, among others, and all inspired by events there, real or imagined. The title story was based on an incident involving an American infantryman, Raymond Norwood Bell. While drunk on sentry duty towards the end of the second world war, Bell shot dead the composer Anton Webern, who had innocently broken curfew by stepping outside a relative's house for a smoke. I'd always been fascinated by the wartime deaths of famous people: the poet Wilfred Owen, for instance, killed by a sniper in the Great War just before the Armistice. Who shot him? Did the sniper know? Did the sniper suspect he might have? Was the sniper himself killed before he found out? The word 'sniper' makes me shiver. War's multitudes of the anonymous dead and missing, of course, leave me speechless. In my story, the fictionalised Bell character finds out what he'd done and is full of remorse, as was Bell himself. I researched him, feeling that he deserved to be more than a footnote in the history of Western music. His family received what today would be called 'trolling' from so-called music-lovers.

Writers should have views about everything moral and political, however ill-formed, and the skill lies in articulating them. My novel, Slowly Burning, is a story told in the first person by a tabloid newspaper 'hack'. Its subject is the voice of the narrator. As a former daily-newspaperman, I wanted to suggest that, for all their faults, these people were not devoid of scruples and common feelings. My latest story, doing the rounds, is based on the Harvey Weinstein scandal. From the deck of a ship chugging up an African river, Graham Greene saw a white man in a white linen suit entering a hut on the riverbank. That brief glimpse of nothing in particular led to his novel, A Burnt-Out Case, about a morally-

impoverished individual finding redemption in the Belgian Congo. Acorns and oaks. I can

identify with that.

Would you recommend self-publishing?

I’ve not tried self-publishing yet, because I’m unable to distinguish it that much from vanity publishing. I hate vanity publishing: it’s cynical on the part of the ‘publisher’, and it’s self-delusional on the part of the writer. I go the traditional route: I submit a script, it’s accepted (or rejected; mostly rejected), and the whole cost of publication is borne by the publishing company. While there are lots of excellent self-published books out there, an author needs a third-party value judgement, and the work needs to be edited. So many S-PBs are badly edited, or not edited at all, even when the publisher being paid by the author says it has been. That’s because authors think they don’t need to be edited, or they totally misunderstand what editing is, what effective syntax is; this attitude is a form of arrogance spliced with cowardice. Some of these books are practically illiterate, poorly constructed and prolix. Having been a daily newspaper sub-editor for many years, I know that every story that came my way could be improved. Why would writers not want their work polished as well as published?

But being published by someone else is no guarantee of a 100 per cent perfect text. There are plenty of discontinuities in writers from Bram Stoker to Raymond Chandler, from Daniel Defoe to Hemingway. Slowly Burning has lots of them; but they are deliberate: the narrator is a former 'Red Top' reporter, and I wanted to illustrate his carelessness and unreliability, though I tried to ensure that his heart was in the right place.

How does your writing process work?

The Graham Greene example illustrates one kind of process, and the idea and the details of what I want to write are similarly vague. I stare at the PC screen for a few

minutes and then start typing, prompted often by a visual image. If it's fiction, the image will turn into a series of images, like a slo-mo film, and I transpose what I see into words. I have a strong pictorial sense, which helps especially with locations, the places where characters will do and say things and which can be described in the form of bearable longueurs, like Hardy's Egdon Heath. By the time I've written a few pages and taken a break, the development of the story, if that's what it is, suggests itself in many ways. This respite time', as I call it, is important: it's when the process of writing becomes open and conjectural, and I entertain all sorts of possibilities, many of which did not exist at the start.

Most often, a story is being made up as I go along – that's to say, it's not a matter of writing down what's already in my head as a detailed sequence from start to finish but creating the detail as I write. If one had the whole story thought out from the beginning, writing it would be just a clerical exercise: the writer as a stenographer. This connection between creativity and giving one's work concrete form at the same time interested the literary critic Hugh Kenner, who believed that operating the mechanisms of writing – pen and paper, typewriter, PC – often influenced what was written and the way it appeared and was expressed.

What advice would you give to new and emerging writers?

Prepare to be disappointed.

There are more writers wanting to be published than there are publishers who want to accommodate them. That said, the internet has spawned multitudes (writers and publishers), many of whom appear and vanish seemingly overnight.

Be ambitious.

There are thousands of small literary magazines (SLMs) out there, print version and digital, both in this country and abroad. For writers, it's truly the worldwide web. But decide whether or not it's an achievement to be published by an online SLM called The Bullfrog & Wheelbarrow Review with a circulation of 54 and edited by a recluse in a Bromsgrove bedsit. Try also the celebrated ones: The New Yorker, London Magazine, Acumen, Agenda, The Paris Review, The Kenyon Review, Poetry London, Harper's Magazine etc., etc. I'm proud of my three rejections from The New Yorker.

Keep a record of your published material.

Most book publishers of fiction, poetry and essays want to see evidence of magazine publication. Include everything, even that epic from The Bullfrog & Wheelbarrow.

Be realistic.

The New Yorker receives about 3,000 stories a month yet publishes only a dozen a year, if that. But even the minnow magazine's postbag heaves with hopefuls. Rejection is usually the view of one or two editors. If they don't like your work, send it somewhere else. But if you receive fifteen rejections of the same piece on the trot, consider its possible flaws and re-jig. Remember, however, that William Golding's Lord of the Flies was turned down by about thirty publishers before it was accepted.

What did winning the Rhys Davies Prize mean to you?

A lot; though it was 16 years before anyone asked me to put a collection of stories together (Funderland, published by Parthian in 2011). The phone didn't ring. But it looks good on my CV. Above all, it was some sort of recognition by peers and an estimate, however skewed, of my worth. But I usually estimate my worth myself, and I'm ferociously self-critical. Most submissions to SLMs require an accompanying biog, so mention of having won a literary prize must register.

Who are your favourite writers, and why?

I don't have favourites. Each book is a miracle of sorts, because I know what's gone into it. Blood, sweat, tears, snatched time, ignoring loved ones, avoidance of

responsibilities – that kind of stuff. And miracles are always happening, the latest for me being the works of the American George Saunders. Earlier, I was influenced by Alice Munro, in whose books I always saw the process of writing behind the words and the imagination at full, sometimes extravagant, tilt. If I don't like a book I assume it's my fault. But there are swathes I regard as rubbish. The popularity of writers is no guarantee of worth. Even with big publishers, the amount of crud they spew out outweighs the gems.

What are you currently reading?

Sense and Sensibility (a re-read); Reading Chekhov: A Critical Journey (a meditation on the Russian writer by Janet Malcolm); and a collection of articles by the distinguished American jazz critic, Whitney Balliett. (Yep: three at the same, multi-tasking time. )

What are you working on?

Apart from any story, poem or essay that suggests itself (these bubble to the top of the think tank unbidden), I'm trying to write a novella about a cantankerous celebrity who moves to a village on the Wales-England border just after the Great War and has a 'fox in the hen house' effect on the community. As Henry James said, something will come.

My second poetry collection, Gwyriad, is looking for a publisher. While it's out there, I keep tinkering with it, and wondering if it couldn't be improved. I fear worrying it to death. Its theme is instability of one sort or another; there's a central section of poems inspired by the place where I live – a converted psychiatric hospital in Abergavenny – and a few visits to the museum of the old Bristol Lunatic Asylum in Fishponds. I've designed a draft cover for it. Everything in this house is home-made. I drew the miner's portrait on the cover of my first poetry collection and designed the collage on the cover of my second story collection. I tried it for one of my latest books, a fictional memoir called Notes From the Superhorse Stable, only to find that my nephew Matt Jarrett's effort outclassed mine; it was the one we

used.

How do you find time to write?

With difficulty. I have no plan. It's a sort of inspired (and productive) lack of discipline, which I quite enjoy. I sometimes attempt the 500-words-a-day régime but it never works. In any case, writers should, for their own sake, be doing non-writing, non-literary things that will, at length, feed into their writing when they get around to it; I mean such activities as watching CrapTV about Australian prisons and taking the kids to rugby and netball practice. Cyril Connolly wrote about 'enemies of promise': those features of a writer's life that impeded creativity. He cited 'the pram in the hall', meaning marriage and domesticity, twin obstacles to what he felt was proper writerly endeavour. Tosh: such 'obstacles' should be turned to advantage. One cannot write about living if one doesn't live. Writing isn't living. This is why I once preferred writers such as Alan Sillitoe to privileged Oxbridge scribes. Sillitoe, who left school at 14 to work at the Raleigh bicycle factory in Nottingham, seemed to me to have more to say about life than tank-topped middle-class scribes and their bourgeois hang-ups. I don't hold that view now; it's too narrow-minded. I tend to read 'blind' as much as possible and allow the text to show me the relevance of what's going on. I leave Theory to theorists; they aren't writers.

Notes From the Superhorse Stable (Saron Publishers, 2022) http://www.saronpublishers.co.uk

Five Go to Switzerland (Cockatrice Books, 2022) https://cockatrice-books.com

Nigel Jarrett is a former daily-newspaperman and the author of five books, including his first short story collection Funderland, which was favourably reviewed, among others, in the Guardian, the Times and the Independent and short-listed for the Edge Hill Prize. His first poetry collection, Miners At The Quarry Pool, was described by Agenda magazine as 'a virtuoso performance'. He is a freelance writer, and his work is represented in the Library of Wales anthology of 20th- and 21st-century short fiction. He is the winner of the Rhys Davies Prize for short fiction and the Templar Shorts Prize. Templar published his story pamphlet. A Gloucester Trilogy, in 2019. His fictional memoir, Notes from the Superhorse Stable, appeared from Saron Publishing in Spring 2022, and his fourth story collection, Five Go To Switzerland, from Cockatrice Books in the autumn of that year. While working in daily newspapers, he was variously a crime reporter, business reporter, deputy chief sub-editor and arts writer. For many years, he was chief music critic of the South Wales Argus. He lives in Monmouthshire and writes as a freelance for Jazz Journal (to which he contributes a regular column titled Count Me In), Wales Arts Review, Nation.Cymru, Arts Scene in Wales, and others.